From Rave Culture to Rx: Schedule 1 Drugs' Therapeutic Potential

This article provides information about ongoing scientific research. It does not provide any medical advice and does not encourage the use of any of the drugs listed.

The history of psychoactive drugs in the United States is a complicated one. LSD, for instance, was originally used in a medical context in the 1950s, and shortly thereafter in secret experiments on unwitting participants by the CIA. In the 1960s psychedelics were used recreationally and even as a form of protest: Dr. Timothy Leary of Harvard advised people to take LSD and “tune in, turn on, [and] drop out” of mainstream culture. In 1970, the Nixon administration instituted the Controlled Substances Act, which made psychedelics and other psychoactive drugs illegal. And, the 1980s war on drugs cemented the idea in the cultural consciousness that drugs which the government labeled Schedule 1 had little to redeem them. But recently, a variety of Schedule 1 drugs have been granted “breakthrough therapy” status by the FDA. That designation allows drugs to be fast-tracked for development after early clinical trials suggest significant therapeutic promise. It’s a long tough road for a drug to have its Schedule 1 designation reconsidered. Schedule 1 is reserved for drugs thought to have a high potential for abuse and no medical benefit. The schedules currently run from 1-5 in the United States, with Schedule 1 including heroin, LSD, ecstasy (MDMA), psilocybin, and marijuana. Cocaine, meth, oxycodone, fentanyl, and Ritalin are in the Schedule 2 bucket, and Schedule 3 contains ketamine, Tylenol with codeine, and steroids.

Classification can be influenced by direct health impact or societal impact, so some designations may seem surprising, depending on your perspective. For example, no one has been shown to have died directly from marijuana or psilocybin, both Schedule 1. However, it has been shown that psychedelics in particular can trigger latent psychiatric illness. As Michael Pollan noted in a recent New York Times editorial, “Someone on a high dose of psilocybin is apt to have badly impaired judgment and, unsupervised, can do something reckless. Without proper attention to setting and preparation, people can have absolutely terrifying experiences...a recent survey of people who reported having a ‘bad trip’ found that nearly 8 percent of them had sought psychiatric help afterward.” Likewise, while fatal overdoses of MDMA aren’t all that common, ecstasy is associated with deaths caused by dehydration, hyperthermia (high body temperature), and heart or kidney failure that occurs when party goers fail to rest or hydrate.

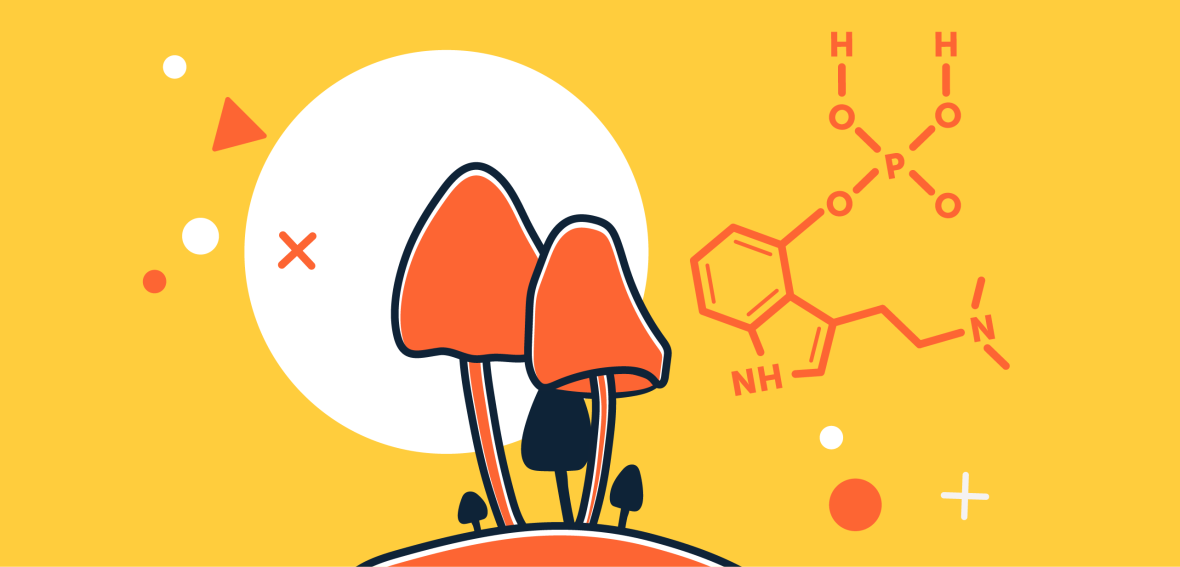

The debate surrounding marijuana’s medicinal properties has been highly publicized with several states allowing medical and recreational use, even while it remains a Schedule 1 drug at the federal level. Less well known are the efforts to test other Schedule 1 drugs’ therapeutic benefits. But in the last few years, psilocybin and MDMA—colloquially known as magic mushrooms and ecstasy—have been the focus of research on how to treat a variety of psychiatric disorders.

Mushrooms are known for inducing visual hallucinations, so it—along with LSD—was associated with the hippie movement’s colorful psychedelic aesthetic and alternative lifestyle. Indeed, psilocybin can induce visual hallucinations like heightened color perception. But in a clinical trial using fMRI, psilocybin has also been shown to effectively reset brain circuits associated with depression and to improve connectivity in the brain.

That’s why psilocybin taken in a controlled setting is being evaluated for its ability to address treatment-resistant depression and end-of-life anxiety in terminal patients: essentially, it rewires associations. For instance, during their clinician-guided psilocybin session, patients were shown images of faces with different emotions expressed. Patients reacted more forcefully to images of negative emotions, like fear. This was surprising—one might assume that reduced emotional response to negative experiences would help with depression—but this indicated a more general emotional responsiveness, which was a good thing. Patients reported “a greater willingness to accept all emotions” and even said that other treatments had “[reinforced] emotional avoidance and disconnection,” according to the Beckley Foundation, which supports such research. Their experiences with psilocybin, though, led to breakthroughs precisely because they were able to confront and resolve emotional trauma. In this way, psilocybin mimicked the logic of talk therapy, but it appeared to condense the successes of long term counseling into just one session.

Despite psilocybin’s Schedule 1 status, taking the drug in a controlled setting with a therapist yielded no serious negative effects, including psychic trauma or physical intolerance, according to lead investigator James Rucker, of King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience. Indeed, psilocybin shows promise as a way to treat drug dependency, particularly alcohol and tobacco addiction. And, there’s evidence from additional FDA-approved trials that it’s a useful intervention for people with OCD and cluster headaches.

While trials using psilocybin target the most widespread disorders, it’s not the only Schedule 1 drug whose therapeutic potential is being explored. Psychotherapy assisted by MDMA (Methylenedioxymethamphetamine)—also known as ecstasy or molly and long associated with the party scene—is also in expanded access trials, particularly to treat PTSD. PTSD patients involuntarily relive traumatic experiences, and PTSD treatment focuses on the relationships that PTSD may interfere with, so some of the clinical trials using MDMA involve couples therapy.

MDMA works according to a somewhat different logic when compared to psilocybin. It increases levels of hormones associated with feelings of joy and connectivity, including serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin (the “cuddle hormone”). The blissful state that accompanies MDMA provides something of a safe space where patients and their therapist can confront troubling memories. While the two drugs rely on different emotional states from which to address trauma or fear, they both help patients confront what they might have suppressed.

That’s what The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) has been arguing since the 1980s, when it started advocating for the use of psychedelics in therapeutic settings. Since then, it has often guided the clinical trials referenced above. According to MAPS affiliate Anne Wagner of Ryerson University, “As evidence accumulates for MDMA’s effectiveness, there is the possibility that MDMA will become legal — a medicine to be used in psychotherapy and prescribed for PTSD.” But if marijuana’s journey towards medical acceptance is any indication, MDMA and psilocybin are in for a long haul.

By Aimee Fountain

References: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

https://www.vox.com/2014/9/25/6842187/drug-schedule-list-marijuana

https://newatlas.com/health-wellbeing/mdma-psychotherapy-ptsd-expanded-access-fda-maps/

https://www.livescience.com/psilocybin-depression-breakthrough-therapy.html

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509636/

https://www.beckleyfoundation.org/psilocybin-for-depression-2/

https://www.drugs.com/illicit/mdma.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/10/opinion/denver-mushrooms-psilocybin.html?auth=login-google

https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/mdma-ecstasy-abuse/what-are-effects-mdma